Reading time: 3 minutes

Literature always saved me. It sounds like a cliché but being a troubled minded teenager having no siblings, and my parents working hard I turned to literature to find the answers I was looking for. I believe books provide us with the life experience and clarity we otherwise need a lifetime for. So many intelligent people are willing to try to explain the world and human interaction through beautiful stories or extensive research gathered in a couple of hundred pages. Having all the books that I want close to me makes me feel privileged.

One author whose stories were an eye-opener to me is Hungarian writer Sándor Márai (1900-1989). Through his eloquent stories, I discovered the outlines of history and why it is better to learn from it. He witnessed two World Wars, turned his back to the Russian communist regime in his country and was deeply moved by the revolution in 1956 that stood no chance against the Russians and the fact that Europe didn’t bother to help.

Márai is the writer who made me realize what topics I wanted to write about. What my style could be. What literature should or could be. Let me explain with a quote from Portraits of a Marriage:

“ But eventually he was forced to realize the human reason is worth nothing because the instincts of the blood are stronger. Passion carries much more weight than reasoning.” one of the antagonists says at the end of the book after witnessing the revolution in Budapest. Márai’s topics are timeless. I read almost the same thing during the American Elections: You don’t win the election with reasonable arguments anymore: Facts don’t matter, populism and infotainment rule.

The end of European middle-class standards (the art of reasoning, for example) is a returning theme in his books, that is relevant to pond about. What if middle class in Belgium disappears? We are losing more and more jobs in favour of new technology. “ Innovation in Silicon Valley means mass redundancies somewhere else.” Rutger Bregman says in his book Gratis geld voor iedereen*. And when the middle class disappears I believe evolution will not make a chance because this is another truth I learned from reading books: it’s our differences that make evolution possible. The middle class has the opportunity & the knowledge, and therefore the responsibility to make a difference. My point is; thanks to Márai I understood that literature can be very relevant to comprehend history, society, people’s motives. They are the antidote for the fast infotainment.

What is history?

You can imagine I was quite delighted when another book by Márai was published in Dutch this year. Er is in Rome iets gebeurd lets the entourage of Caesar talk in the night after his murder. Twelve hours, twelve chapters, twelve people talk about the death of the dictator: slaves, eunuchs, lawyers, senators, and mistresses all get their five minutes of fame in Márais book.

“What is history?” the writer Lucceius asks Atticus, the well-known editor and friend of Cicero in the last but one chapter. Atticus replies: “Not the battles and conquers. Nor the triumphs. (…) the wars and the quarrelling in the Senate. Write down that other history, the real one. (…) Describe what the mistresses, eunuchs, lawyers, senators tell on a day like this. Show that history is not a chain of particular events but rather something constant and tedious.”

Like I said, the main power/attraction of literature is that we can understand history better. This is not new but Marai nuances this by bringing people who really existed in ancient times. Atticus was a well-known businessman and close friend of Cicero. By doing so, Márai brings the responsibility to its people- or if you want, to its readers- and not to some untouchable, historical fact or political body. Yes, the entourage of the dictator does not represent the common people like me and you, but in this book, they are depicted as common people with their own desires, passions, hypocrisies… One can easily recognise its own entourage in it, may that be a volleyball club, local café or neighbourhood council.

“The lesson I learned from this wonderful book: we are the history.”

Off course as long as we don’t learn from our mistakes, history repeats itself after every generation and Márais books can stay timeless. Our mind could use a paradigm shift. It is something we have to start believing in: that common people do can influence politics. That market economy is not something we cannot grasp but is in fact established by real people, may that be bank managers, the CEO of a multinational or the president of a commission… A handful of people with the same basest instincts or impulses as in ancient times, a handful of people we can easily trace down if we want.

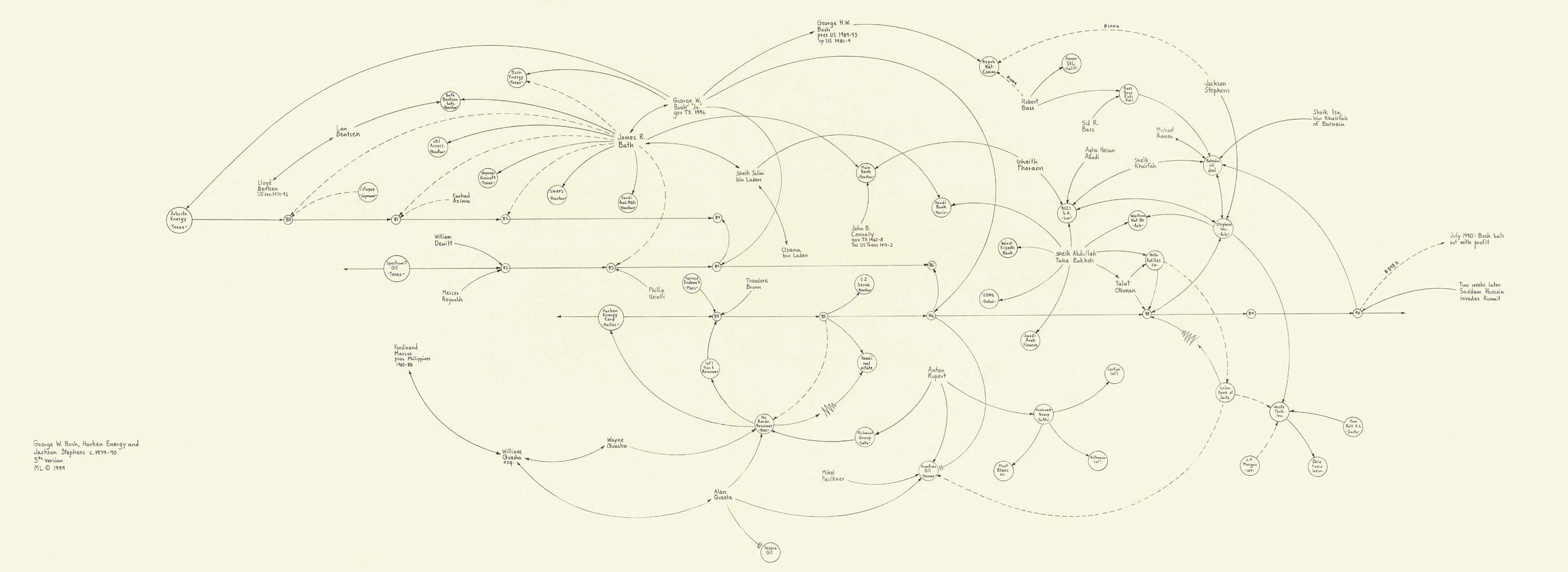

This is why I love the work of American artist Mark Lombardi (1951-2000) who neatly encapsulated the global networks of political, social or economic structures in very accurate diagrams (he called them narrative structures). He condensed huge amounts of data into useful schemes that are both aesthetic and informative. He exposed very complicated connections between George W. Bush and Osama Bin Laden, fifty years of organised crime in Chicago, the global flow of money, and made it understandable for even simple people like me and you who can visit his work in musea.

So, the lesson I learned from this wonderful book: we are the history. Not the CEO who puts his signature beneath a million dollar contract, nor the multinationals or the legislative powers that change every couple of years, but for us, the people. The 99% you know.

* Rutger Bregman, Gratis geld voor iedereen, p. 75